In a Time of Crisis, the Kyrgyz Nation Unites to Help

When a government emergency initiative to help displaced citizens along the Tajik-Kyrgyz border came underway, the people of Kyrgyzstan demonstrated their generosity.

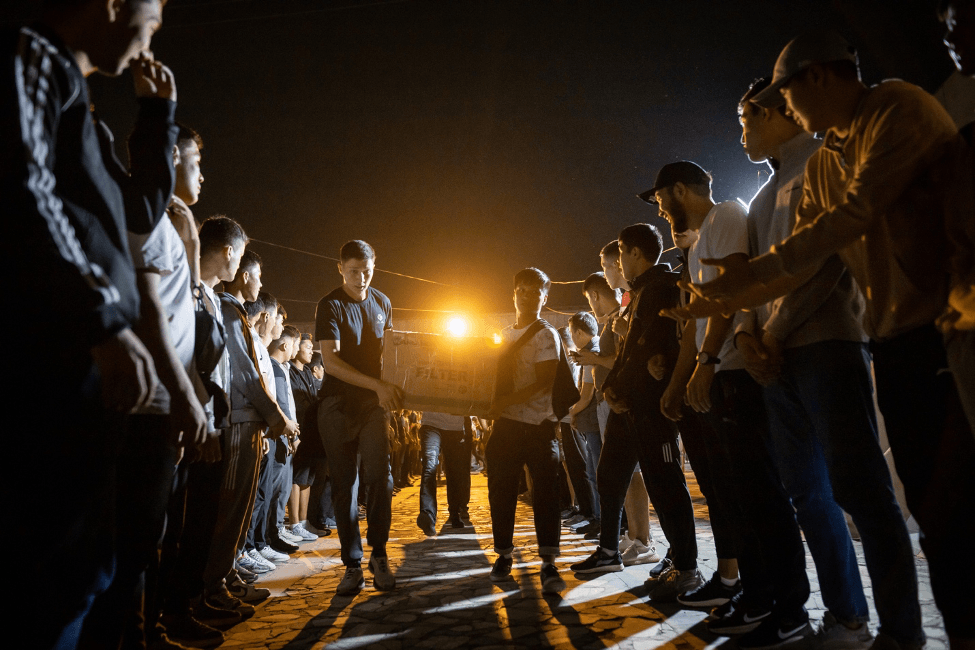

Volunteers outside one of Bishkek’s main multipurpose event venues, Kojomkul Sports Palace, create a human corridor for those carrying aid to delivery trucks. Just days earlier, Kyrgyzstan launched its most-ambitious humanitarian aid initiative, Batkenge Jardam (Help for Batken), responding to the needs of displaced citizens of Batken after a border conflict between the countries of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan shook both nations.

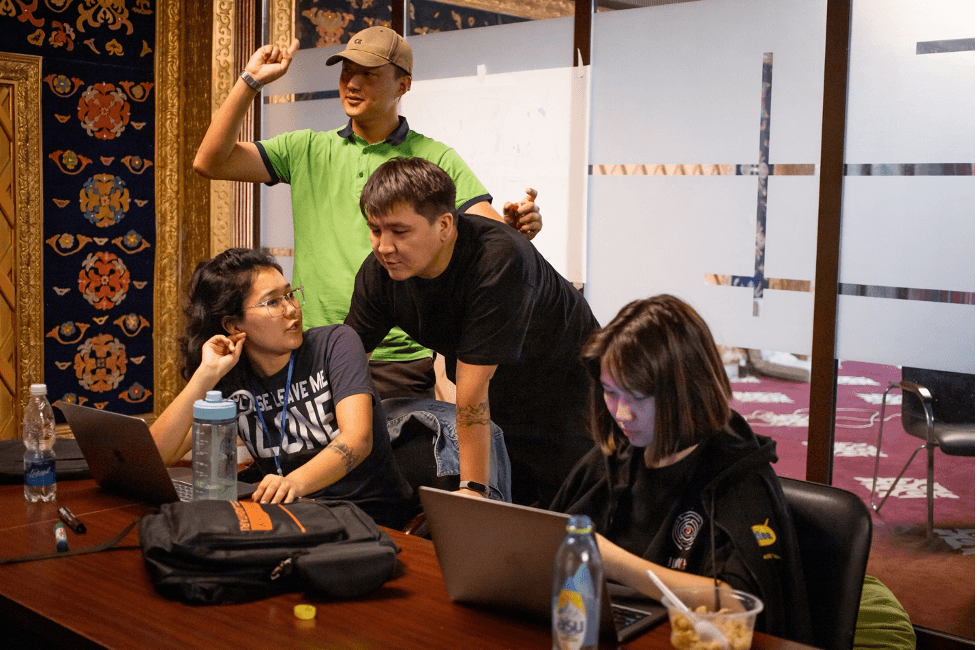

Sitting in the main hall of the Kojomkul Sports Palace, one of Bishkek’s three largest multipurpose venues, temporarily serving as a drop-off point for donated humanitarian aid, Kamila Usmanova, a spritely university student, busies herself as a liaison between displaced citizens hundreds of miles away and organizers behind one of Kyrgyzstan’s most-ambitious humanitarian aid response program in years. Usmanova struggles to find her focus, but it’s hard not to become lost in thought over the tens of thousands of lives displaced by the recent conflict unfolding in Batken between Kyrgyz and Tajik border forces.

A social media coordinator working in the press center of the republican headquarters of Batkenge Jardam, literally “aid for Batken,” Kyrgyzstan’s southwest region bordering Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, Usmanova was determined to find enough shelter, food and clothes for those of Batken forced to flee their homes. With her laptop in front of her, she jotted down and organized requests from calls flooding in from volunteers serving as conduits for displaced residences, careful to expedite every appeal for help that came her way.

Clashes first broke out in Batken along the Kyrgyz-Tajik border on September 14, 2022. Batkenge Jardam, an emergency initiative spearheaded by the Kyrgyz Minitry of Emergency Situation, immediately responded. But to see results, Batkenge Jardam would have to galvanize everyday people to show up for support. This is where Usmanova and her team proved essential: they would have to harness the strength of social media to get the support needed, on Instagram, Facebook and other channels, through daily updates and appeals for help. Volunteering as a social media coordinator for the initiative’s public relations team, Usmanova recognizes how her up-to-the-minute reporting amplified Batkenge Jardam’s cause and instilled public trust through transparency. “People should see and know what is going on,” says Usmanova.

More than 3,000 volunteers descended upon the Sports Palace to actively give their time and energy to help their Batken compatriots. Among them, university student Kamila Usmanova, shown lower left, coordinating with colleagues requests for aid she had just received from frontlines of Batken.

Within days after the team’s first post on September 16, Batken Jardam saw thousands of volunteers rushing to the sports palace, the usual gathering spot in times of crisis, a place of unity and solidarity. In total, 3,157 volunteers descended upon the venue, converting it overnight into a drop-off point for necessities Batken evacuees, hundreds of miles away, would need, from food and clothes to blankets and pillows. In the five days Batkenge Jardam was operating, people from across Kyrgyzstan’s capital donated more than 1,000 tons of humanitarian aid in the form of food and clothes, says Nurmukhammed Atambaev, a specialist at the Ministry of Culture, Information, Sports and Youth Policy.

In the five days Batkenge Jardam was operating, people from across Kyrgyzstan’s capital donated more than 1,000 tons of humanitarian aid in the form of food and clothes.

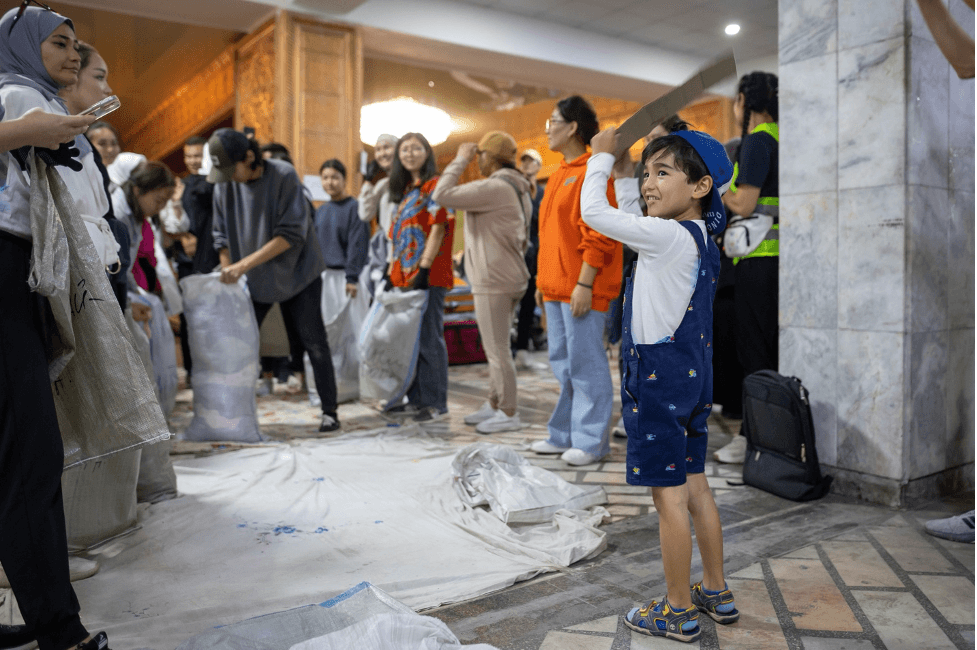

As humanitarian aid poured in, groups of volunteers, each responsible with its own mission, sorted and registered each item separately to ensure total transparency. From there, other teams distributed, counted, labeled and packed the aid for delivery. Finally, young men, lined up in rows across the palace’s vomitorium, forming human conveyor belts that seamlessly rolled boxes and bags from one set of hands to another into box trucks. All the while, young women stood nearby to provide much-needed relief from the palace’s humid environment by waving in back-and-forth motions make-shift hand fans from pieces of cardboard box.

Usmanova and her team took note of every tiny bit of work by volunteers. They captured all the most-significant and -touching moments: young children coming in to help with small tasks; volunteers lifting their voices and spirts, singing Kyrgyzstan’s national anthem in between loads.

Outside the Sports Palace, volunteers pause to sing the Kyrgyz national anthem.

A child at the Sports Palace provides much needed relief for volunteers from the palace’s humid environment with a makeshift fan of cardboard picked up along the way.

Within five days, between the 16th and 21st of September, Usmanova and her team worked around the clock to account for each donation made. Each day, Usmanova saw herself toil over multiple jobs, sometimes as long as 12 to 14 hours. “She worked for four days, from morning to late night,” Atambaev says.

Although Usmanova proved to be steadfast, nothing could have saved her from the emotional pressure she contended with after the clashes broke out. Never-ending news from the border, stories of families in danger and the relentless flow of calls and messages from volunteers in Batken continuously intensified. The organizations in Bishkek had to be quick with their response timing. The processing, procurement and distribution of aid depended on the intensity of work from Usmanova’s team. Feeling the strain of it all, one night after another long shift, Usmanova broke down. “I was feeling anxious. It was very hard,” she confesses.

These events have shaken me up. After that, I got myself together and said, ‘I should help.’Aijamal Maneva, university student

Aijamal Manaeva, a university student in Bishkek involved in volunteering from the very first day, sympathizes with Usmanova. Studying full time at the American University of Central Asia (AUCA), Manaeva was already on edge when the situation on the border emerged. And like Usmanova, she never thought twice about volunteering. “These events have shaken me up. After that, I got myself together and said, ‘I should help.’” Manaeva says.

Seeing what Batkenge Jardam had achieved and how the country had pulled together inspired Manaeva to gather her fellow students at AUCA and organize her own fundraiser for Batken. Having already worked as a volunteer, she felt confident about her commitment. “I feel better, and I feel useful when I help people,” she says.

Two volunteers work together to categorize and register donated aid inside the main hall of the Sports Palace. It wasn’t uncommon for volunteers to devote as much as 12 hours a day receiving, counting, sorting, labeling, logging and loading donations received over the course of five days, between September 16th and September 21st.

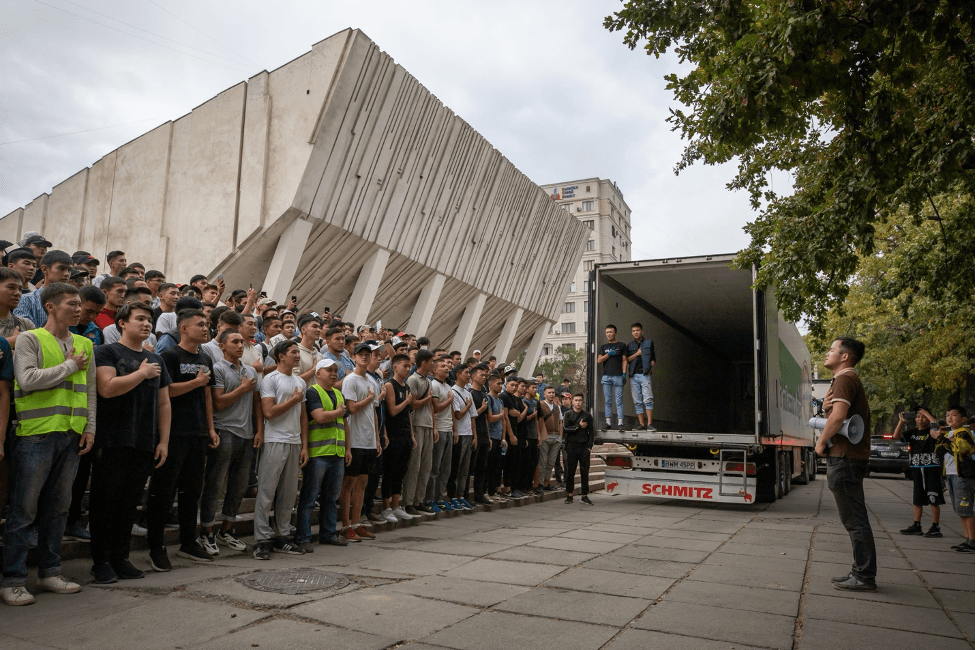

Young volunteers load essential supplies like clothes and food into box trucks to be delivered to Batken. In total, more than 1,000 tons of humanitarian aid was received and distributed.

Such sacrifices are not uncommon in Kyrgyzstan. People adjust to what is a cruel reality: conflicts and disaster happen regularly, and often the only help that those in need can count on is the help of their fellow citizens. “We are used to handling things ourselves. We have it embedded in our culture: we will never leave our people in trouble. It is like brushing our teeth in the morning,” Manaeva acknowledges, shrugging her shoulders.

Atambaev agrees, as he points to the deep cultural meaning of generosity among his fellow countrypeople. The Kyrgyz, much like other Central Asian Turks, participate in ashar, the time and work people give for relatives and neighbors, for example, to build homes.

Atambaev also points to historical demonstrations of Kyrgyz generosity. In the 1930s, for example, some 1.5 million people died during a three-year famine, because of a zhut, the mass starvation of livestock, and from collectivization that was implemented just a few years before. The Kyrgyz had responded by sharing as much food and clothing with their brothers and sisters in the north. “The Kyrgyz helped with more than 1,000 people. We hosted them and fed them for several years,” Atambaev says.

Today, because of the people’s generosity, fundraising for Batken has matched the historic responses of the past. In a country where the annual household income per capita has only recently reached $900, the people of Kyrgyzstan have successfully collected and distributed 1,000 tons of humanitarian aid and dispersed some 17 million Kyrgyzstani soms (equivalent to about $211,000) within a five-day period.

A volunteer proudly showcases his Kyrgyz flags, which are hoisted on a shopping cart used to move relief aid to transport trucks.

And that has registered with Usmanova, who, having worked tirelessly at the Kojomkul Sports Palace for nearly a full week, can now relax knowing her efforts paid off. For her, it hadn’t been about the numbers. The experience had always been about how volunteers were able to impact the lives of the people they helped—about what they could always do with their generosity.

“I think our people will always be ready,” she says, “I hope this does not happen again, but we are always on the alert.”