How a Kazakh Teacher Keeps the Spirit of Nauryz Alive

In a rural village in eastern Kazakhstan, 75 kilometers from the country’s border with China, a local teacher has galvanized her fellow residents for the last 25 years in reviving a holiday that was once banned during the Soviet Union.

In the village of Akbulak, faculty, students, parents and local residents have gathered at the local school every March 21 to celebrate festivities for the spring new year, Nauryz. The food and activities have been a collective effort spearheaded by one of the school’s very own teachers, Sagdat Samanova, seen on stage, center, giving an introductory speech.

Mid-March has once again rolled around, and in the otherwise sleepy village of Akbulak, some 75 kilometers west of Kazakhstan’s eastern border with China, excitement brews among its 375 residents as the pageantry of spring reveals life anew. Warming temperatures have begun to melt the winter snow and the birds perched above quaver and trill. Among the village’s longtime residents is Sagdat Samanova, who fashions her traditional Kazakh koylek, a flowing camisole adorned with intricate embroidery, and a shawl as she leads preparations for the spring new year, just as she has since the late 1980s. She rubs her hands through an admixture of entrails and cow fat, carefully marinating it with salt, garlic and pepper. Soon she will be using what is in front of her to stuff the internal casing of the thoroughly cleaned small intestine sitting in water next to her, tied at both ends, before smoking and drying it. For Samanova, this sausage delicacy, shuzhuk in Kazakh, reveals a much larger story of renewal for the nearly forgotten Persian New Year Kazakhs celebrate every March 21 .

Sagdat Samanova, above, has dedicated the last 25 years, since 1988, in gathering her fellow residents of Akbulak to celebrate the traditions of Nauryz she once enjoyed as a child. Today, Samanova is known as Sagdat apai, a respected elder sister, who younger people seek for blessings.

Samanova has dedicated the last 25 years—since 1988—to reviving Nauryz traditions she once experienced as a child. But all that was nearly lost during the Soviet period, when for decades Nauryz celebrations were forbidden. “Every year when I make preparations for Nauryz, I feel great excitement that finally we can celebrate it officially in the way our grandparents did”, Samanova says.

And it’s because a large part of Nauryz traditions unfold at the dinner table that Samanova focuses so much energy in preparing dishes her own grandparents once prepared for the holiday. With each meal she prepares, Samanova, like other Kazakhs, ensures that Nauryz customs and beliefs extend beyond symbolic meaning, such as the rejuvenation of nature, of fertility and sanctity, and are passed onto the next generation.

Nauryz, spelled Nooruz in Kyrgyz and Navro’z in Uzbek, commemorates the birth of spring and the end of the harsh winter, with three days of coming together that begins at sunbreak on March 21. “My mother, Kanipa,” Samanova, a teacher at the village school, now in her 60s, points out, “used to pour milk into a cup and splash it in the direction of the rising sun and would say to the sun, ‘Oh, Mother Earth! Oh, Holy Mother Earth, please bless my people and my family. May the evil be away from us, may all of us have peaceful life, may us be in solidarity and cohesion!’”

And with those first rays of sun, Samanova begins making kozhe, a chilled broth of milk, mutton and grains. While there are many ways of preparing the dish, she chooses ingredients based on color: water for blue, meat from slaughtered livestock and frozen for red, milk and other dairy products white, wheat and grains green, butter yellow, noodles brown and salt black. But the most important ingredient comes with a smile, says Samanova’s 41-year-old son Zhasulan, recalling his mother’s advice while cooking. “A person who cooks Nauryz kozhe should be in a good mood, put some sense and all positive energy into it,” he says.

And that positivity spills over into the generosity that surrounds the spring new year, for Nauryz among the nomadic societies of Central Asia marks a turn from a season of meagerness and hardship that comes with the onslaught of winter to the abundance that spring promises. One can see this on the dastarkhan, the traditional tablecloth spread on the ground for eating, in most Central Asian cultures. The bigger the dastarkhan and the more variety of dishes, the more assurances families will receive of a year of plenty and prosperity.

Under the influence of Persianized speakers, Nowruz, the former name of the holiday Uyz was changed to a new one—‘Nauryz.’Bakhyt Kairbekov, Kazakh poet and screenwriter

But a year of plenty also provides incentive for sharing, and Samanova relishes the opportunity to welcome friends and neighbors in sharing in the spring blessings. On Samanova’s dastarkhan, guests can find in addition to shuzhuk and kozhe, zhent, sweet millet flour made of butter—much like halva—cottage cheese, sugar or honey, baursak—small pieces of fried dough—kurt, made from dry fermented milk, jams and other traditional dishes. One such neighbor is Batima, who recognizes the warmth and generosity behind Samanova’s efforts. “Sagdat is a very generous and hospitable woman. When it comes to baking, she is a talented cook. Sagdat always lays a table full of various meals for Nauryz,” says Batima, 72, a retired nurse.

The Nauryz spread Samanova has laid out across the dastarkhan goes back generations, even millennia, to the heart of nomadic civilization across the Kazakhstan steppe. At the T. K. Zhurgenov Kazakh National Academy of Arts, in Kazakhstan’s capital of Astana, social anthropologist and historian Evfrat Mambekov insists that Zoroastrianism reached early Iranian nomadic groups like the Sogdians some 3,500 years ago, who eventually brought their customs with them when they began to roam what is now Kazakhstan. But, Mambekov, is quick to point out that Nauryz originated with the proto-Turkic nomadic groups already living there. “Nauryz is the most ancient holiday of the peoples of equestrian nomadic civilization,” Mambekov says, noting, “It spread from the depths of Central Asia to the Mediterranean. Nauryz was originally born in Kazakhstan.”

Sagdat Samanova, center, wearing a red shawl, gathers with parents, faculty and friends in front of a table set with Nauryz traditional dishes. Nauryz provides opportunity, as it has done for generations, to welcome others in sharing traditional Kazakh food and well-wishes for the spring new year.

Bakhyt Kairbekov, a poet, film director and screenwriter, concurs with Mambekov’s theory, as he focuses on the etymology of the holiday’s name. The universal rendering of Novruz is a Persian compound word, that when broken apart means new day. The Turkic peoples, before making contact with Iranian nomadic tribes, had their own holiday that commemorated the first of spring and uyz, colostrum, the first form of milk produced by cattle mammary glands, known for its purity and wholesomeness. “Under the influence of Persianized speakers, Nowruz,” Kairbekov says, “the former name of the holiday Uyz was changed to a new one—‘Nauryz.’”

But it wasn’t until the early years of the Soviet Union that Nauryz was banned across Central Asia. In Kazakhstan, that was 1926. It wouldn’t be until 62 years later in 1988 that Kazakhstan once again celebrated the spring new year. Gulbakyt Tanybayeva, a retired accountant and former resident of Akbulak, remembers well how the entire village pitched in for the festivities of the spring new year. “Every organization, including the hospital, high school, kindergarten, post office and others assembled their own felt yurts and decorated them in traditional styles with banners filled with blessings, storage chests, national felt carpets,” the 71-year-old recalls.

Fellow resident Gulnar Raimkhanova presents her neighbor, Samanova, a recently hunted fox that has been cleaned and preserved for its fur. Among Kazakhs, such gifts are given to respected individuals.

Samanova, known endearingly as Sagdat apai (apai being an honorific title for older women) by locals of Akbulak, also recalls how everyone pulled together to make that first Nauryz memorable. “Children and young people played traditional games such as asyk atu,” she says of the nomadic game of sheep joint bones, in addition to togyz kumalak, a form of the board game mancala, kokpar, the game in which two horse riders for a goat carcass. “In 1988, for the first time since the Soviets ahd come, Samonova says, “an altybakan, a large swing, with colorful decorations was assembled in Akbulak.

The significance of that first Nauryz in other parts of Kazakhstan is not lost on those that remember. “By reviving Nauryz, we, kazakh people returned to our roots, to our traditions, to ourselves, to our culture and philosophy,” says Mambekov.

And that revival of Nauryz in Kazakhstan in 1988, Mambekov points out, was because of the efforts of one person: Uzbekali Zhanibekov, the then minister of culture. “As a public servant, Uzbekali Zhanibekov could not openly request a public celebration of Nauryz, and for this reason Shakhanov Mukhtar as a poet, a master of words became the mouthpiece of the initiative. Shakhanov, Roza Baglanova, a famous Kazakh singer and other people from the creative intelligentsia of Kazakhstan spoke up for the revival of Nauryz,” Mambekov says.

But all of that would not have been possible had the December 16, 1986, tragedy of Zheltoksan never occurred. According to Mambekov, Zheltoksan was the first public protest of its kind within the Soviet Union against the imposition of foreign culture at the expense of local ones, and Moscow two years later had little choice but to comply with the wishes of Kazakhs so as to not add more fuel to the fire. “Moscow administration could not do anything but permit to celebrate it officially,” Mambekov, who also participated in the Zheltoksan protests, proudly declares.

Fellow residents of Akbulak work together in preparing kozhe, a chilled broth of milk, mutton and grains that have become a representative of Nauryz celebrations across Kazakhstan.

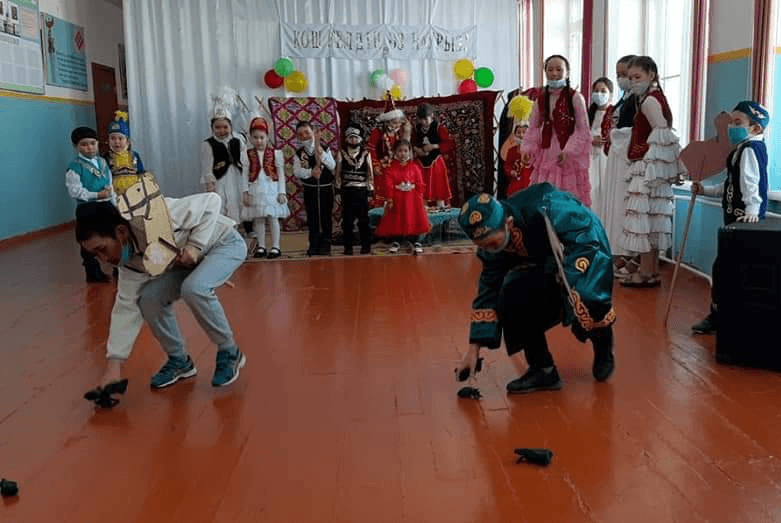

And because of those national heroes, various legends about the origin of Nauryz are constantly born and shared in places throughout Kazakhstan. In Akbulak, where the revival of Nauryz and the continued preservation of its traditions remain strong, Samanova has gone so far as have her students re-enact the origin of the first spring new year. “I tried to make my own play about the origin of Nauryz and let my students demonstrate it at school ever year,” Sagdat apai says.

According to the myth behind the play, a small boy approaches his grandfather and asks about the origins of Nauryz and learns that one biy, lord, Kumia, had two sons Nauryz and Alash. While Alash had many children and grandchildren, Nauryz had no offspring. So, with the arrival of each spring, Alash’s descendants would come together to visit and congratulate Nauryz on the new year. To welcome Nauryz’s brother’s progenity, Nauryz’s wife would cook up soups of various beans and herbs and treat the people of the village to a celebration. In old age, Nauryz ata, respected father, as he was by then known made one wish: to remember his name every with the coming of the spring new year.

As part of the Nauryz celebrations at the local Akbulak school, students reenact the origins of Nauryz in a play written and directed by Samanova.

Ainur Saripova, a former student of Samanova, credits her former teacher and the play with having such a profound impact on the residents of Akbulak. “I remember how Sagdat apai let us put on different plays on holidays and important historical events. She always tried to create some plays, write poems related to our history, customs and traditions,” Saripova says.

Samanova’s former student, Ainur Saripova, shown sitting in a yurt set up on the grounds of the Akbulak local school on the eve of Nauryz, credits Samanova for having such a profound impact on the residents of Akbulak.

For other residents, like Gulnar Raimkhanova, Samanova’s neighbor, Samanova embodies Nauryz, for it’s the elders who bless the younger ones, and as one Kazakh proverb states, blessings make people green with peace, prosperity and friendship, like the rain makes the earth green, and that is the first sign of Nauryz. “Sagdat is a respected person in Akbulak, and it is quite customary for youngsters, her former and current students, as well as neighbors to seek out blessings from her,” Raimkhanova says.

As Samanova finishes this year’s festivity preparations, she extends well-wishes for her own family and fellow residents with the upcoming Nauryz: “May the sun pour its sunshine on this family, bring them peace and safety, and may they be healthy and have a happy Nauryz!”