Houston Kazakh School Creates Sense of Community

A local Saturday school for Kazakh children in Houston provides a worthwhile lesson in community building.

On a Saturday in mid-September, inside the second-floor salon of Houston’s Raindrop Turkish House, a community center serving the city’s many Turkic citizens, some two-and-a-half dozen Kazakh families are convening. For the past hour or so, parents have filled the sofas lining the outer parameter of the room. Today marks the first day of Houston Kazakh School, a community Saturday school for the more than 40 children sitting cross-legged across the floor in front of them.

Students within the zhiger class (ages 7 years to 10 years) enjoy pizza during a break from lessons.

At the helm of the room, all eyes dart to Kazakhstan-born Indira Setzhan, a 45-year-old mother of three. Sporting a black blazer over a black-and-white striped gown, and with her hair pulled back, she picks up a metal serving tray filled with heaps of candy. Suddenly, she casts all of it by the fistfuls into the air, sending the throng of nearly four dozen Kazakh children, ages 4 to 10 years, into a frenzy. As if on cue, half a dozen women converge near the door to usher the children away to their classes, divided by age range: balapan (ages 4 years to 6), zhiger (ages 7 years to 10) and alash (ages 11 years to 13).

But the more teachable moments seem to come through with the parents, who appear unable to mask their enthusiasm. For many of them, the occasion marks the first time since COVID they have been able to come together. For those attending today’s opening, all from Kazakhstan, the Saturday school does more than just provide a rare space for socialization among familiar faces. It reinforces community building, as Setzhan demonstrates with zeal. “We only met two or three times (in less than a month), and we just opened it, [saying] ‘We’ll see [how it goes],’” Setzhan says of how eager they were to get things going for the year.

Students learning dance routines at the Houston Qazaq School. Photo by Houston Qazaq School

Since 2012, the school has offered opportunity for Kazakh children and parents alike to build a sense of community. Setzhan points out how the children look forward to attending Houston Kazakh School for the lessons as well as the opportunity to build long-lasting friendships. “They want to see their friends, sometimes dance, sometimes play the dombra,” she says of how the children begged for the school to start back up for the new academic year.

Maulen Uteuliyev and his wife, Elvira Uteuliyeva, both in their late 30s, are parents to three of the children attending the school. Both recall when the school opened its doors for the first time in September 2012. Back then the school grew out of an effort spearheaded by the then newly established Shanyraq Foundation, a nonprofit organization serving the Kazakh community of Houston. It was one of the selling points that convinced the Uteuliyevs to move to Houston the same year from San Diego, California. “When my husband said that Houston had a Kazakh community and they’re planning to open a Kazakh school, I said, ‘That’s great! Let’s move there,’” Uteuliyeva says.

Back then, the school, the first of its kind for any Kazakh community in the United States, had less than 20 students, they recall. Because of the few Kazakhs in Houston then, parents and community members tended to work double or triple shifts in overseeing the operations of the school while also providing lessons in language, culture and STEM, and on playing the dombra, the Kazakh national instrument.

Uteuliyev served as part of an advisory committee for the school till 2018, while Uteuliyeva volunteered as both a curriculum developer and teacher. With only a limited number of students, the school divided the children into two groups by age: balapan (meaning chick in Kazakh, ages 3 to 6 years) and tulpar (foal in Kazakh, 7 to 12 years). “There wasn’t a very big Kazakh community at the time,” Uteuliyev notes.

But the school, just like the population of Kazakhs in Houston, exploded in size, seemingly overnight. Within a couple years, the school had grown from a handful of families to around 20, with most committing their time and energy to the development of the school as well as some quality community building.

While students checked into classes for three to four hours every Saturday, for example, parents busied themselves by engaging in social activities. Tea for the women, volleyball or soccer for the men and birthday celebrations for everyone. Soon, other adults—even those without children and or those from outside Houston—would hear about the program. They too would devote themselves to volunteering at the school for the sole purpose of experiencing that sense of community. For once a week, every Saturday, the Houston Kazakh School, Uteuliyev says, “became like an epicenter, a center that people join.”

Indira Setzhan has led the Houston Qazaq school since 2012, much like she leads a troupe of Kazakh students on stage for dance performance in celebration of Nauryz, the Spring New Year. Photo by Houston Kazakh School

And those numbers would double when the school organized school events like school picnics and concerts throughout the terms. Events celebrating Kazakh Independence Day (December 16), Women’s Day (March 8) and Nauryz (March 21) would draw in upward to 40 or 50 families and bring in Kazakh university students and other singles as well. “Bonding became stronger between the community,” Uteuliyev says of the outcome, “not only for the parents of the students but also for the people who didn’t have kids in the school.”

Bota Sadykova, 39, a mother of three, teaches elementary students at a local primary school in Houston. Having lived in Houston during the late 2000s before moving away, she has seen the city’s Kazakh community grow from a small group of oil engineers and professionals to upward of 5,000. She says the school provides an atmosphere for individuals to bond and build a deep connection. This is especially important as most feel the effects of separation from families back home in Kazakhstan. “We Kazakhs are kind of social. Here we don’t have that as much. We don’t have our family or extended family. So that’s why we feel very close as a family here.”

The emphasis most Americans place on individualism and independence, Sadykova also mentions, plays a huge part in building bonds at the school. Most Kazakh families sense the process of asking for help from others outside the community as daunting, Sadykova adds. “I could drop off my kids at my mom or brother’s house [in Kazakhstan],” she says, “but here we don’t have a family. We don’t have an option to ask our friends or our neighbors.”

Setzhan likewise alludes to this when talking of the impact of the school. Instilling a sense of family both for the adults and children remains central to building community, she says before adding, “I want my kids to be raised inside the Kazakh community—to be a son or brother for everyone.”

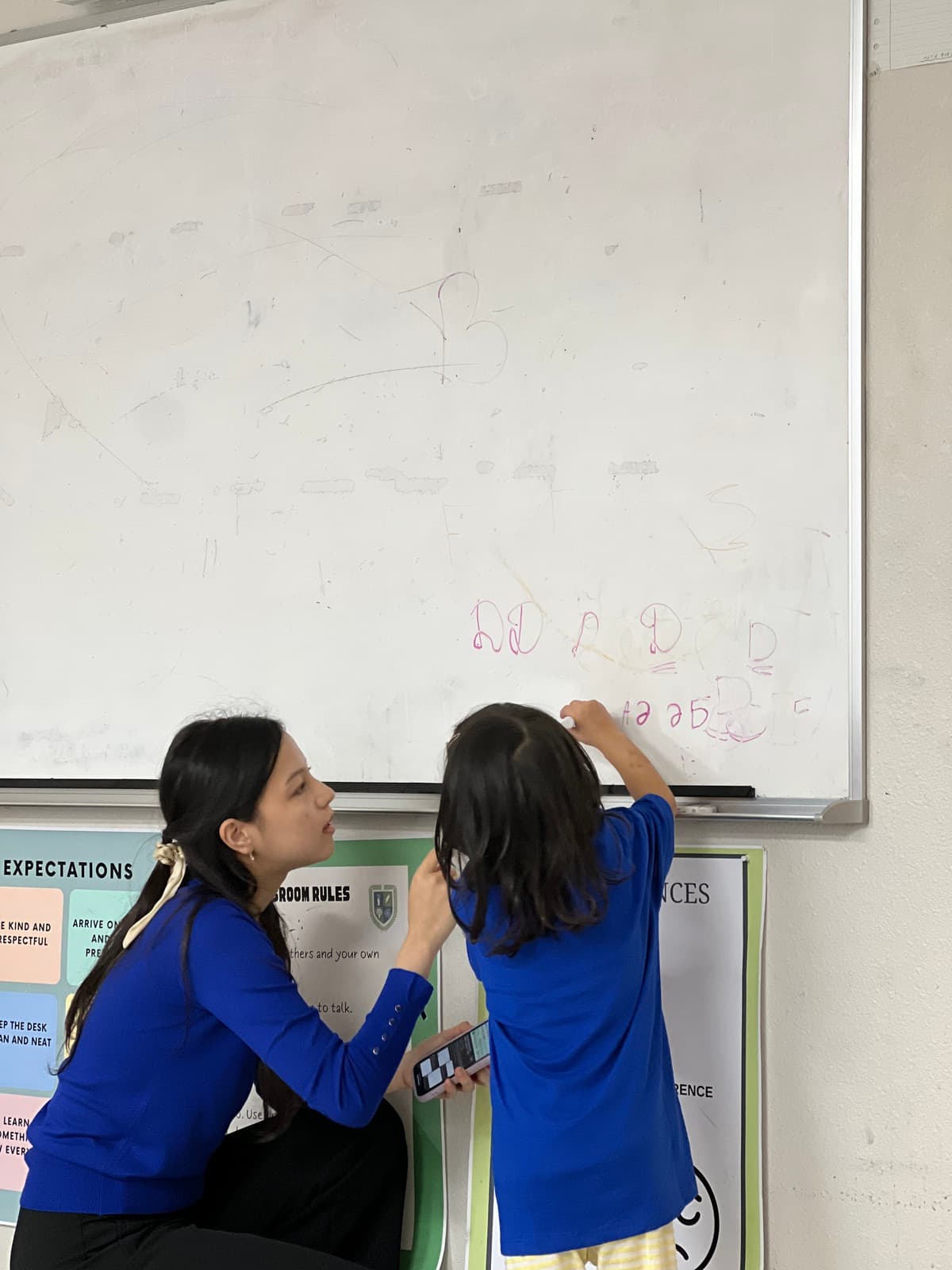

Parents volunteering to cut out decorations for students. Photo by Houston Qazaq School

The connection between each child and parent has helped the community retain its cohesiveness so much so that even COVID did little to interrupt classes for two years in 2020 and 2021. So strong was the urgency to resume some aspect of the school during that period that parents lobbied even to have even just Kazakh language lessons virtually during the 2022–2023 school year just to maintain that sense of community.

But, Uteuliyeva says, the transition to in-person lessons from offline has proved seamless. “It was not like we struggled to move from online to offline. It was smooth, and everybody was like, ‘Okay, I’m ready. Yes. Let’s do it,” she says.

Uteuliyeva attributes that seamlessness to in-person classes to the enthusiasm parents and others have demonstrated in volunteering. While children receive their lessons, some parents guide students as hallway monitors, others walk from classroom to classroom distributing snacks and drinks to the children, and still others go so far as ready classrooms before school and clean the premise after it ends. “Parents are happy that they can contribute even a little bit. They do care that they can do something for the school,” Uteuliyeva says.

Sadykova agrees. For her, volunteering at the school safeguards the continuity of the community. “It’s like an investment in the future generation, that if I’m able to do that, then my kids will learn from that.”

As the evening of the first day of Houston Kazakh School comes to a close, Setzhan revels in having outlined the goals of the upcoming school year. For her, the parents in attendance allow the school to continue and the community to thrive. “I appreciate Kazakh volunteers helping at the school. It’s important for the kids to be able to grow up together,” she says.