Edgu Bilig, a New Online Magazine, Set to Make History

When a small group of women gathered in early 2021 to launch an all-English magazine, little did they realize they would be making history too.

Dinara Assanova, above, founder of Kazakhstan’s first virtual museum on the history of women, Women of KZ, speaks at a roundtable discussion at the 2018 Women at the Silk Road conference. By 2021, she would go on to found Edgu Bilig. Photo Credit: Dinara Assanova

On a late April evening, shortly after 8 pm, Dinara Assanova hurried through the door, kicking off her shoes at the entrance, and darted straight to the kitchen of her high-rise apartment in Kazakhstan’s largest city, Almaty, where she lives with her two young daughters. After scrambling toward the refrigerator, she flung its door open and wriggled her way deep within its chambers for anything that would make for a quick meal. Tossing one item after another from the fridge, she worked frantically as she balanced her phone between her ear and shoulder. Once again she found herself late for her weekly virtual call. Just a few moments before, she had rushed to message the group, “On my way, driving.”

Assanova, the founder of the first virtual museum on the history of women of Kazakhstan, Women of KZ, and a Ph.D. researcher, excused herself before greeting the four others she was joining on the call: an independent scholar from Uzbekistan now living in Texas, near the Mexico-America border; a Kyrgyz journalist who at the time was finishing her master’s degree in Saint Petersburg, Russia; a documentary photographer from Kyrgyzstan; and an American Turkologist from Houston, Texas. The five of them first began to regularly convene in 2021 over Telegram and Skype to set in motion plans to launch an English-only digital magazine dedicated to Central Asians. Much like the others, Assanova, juggled family life, an academic career and full-time work.

Dilbar Akhmedova moved to the United States from Uzbekistan as a graduate student studying comparative Turkic literature at University of Washington, Seattle, where she actively helped fundraise for Uzbek diaspora communities in the area, such as for this traditional dance ensemble she fundraised for back in 2016. According to Akhmedova, an original founder, the magazine “opens a new school of international journalism for journalists” from Central Asia. Photo Credit: Dilbar Akhmedova

But the team viewed their struggles in terms of the monumental outcomes before them. What they were about to pull off would be nothing short of historic, they understood. For starters, they saw that as four women representing Central Asia’s largest ethnic groups working together, they were achieving a feat never attempted. This compelled the group forward, with each determined to challenge the other, if only to reach another historic first: to change the world’s perception of Central Asia by having local writers engage a global readership through shared positive, transformative human-interest stories from the region. “What this journal does is unique,” said Dilbar Akhmedova of Uzbekistan, who joined Assanova in the virtual meetings, adding that, it “opens a new school of international journalism for journalists” from Central Asia.

What this journal does is unique. … [It] opens a new school of international journalism.Dilbar Akhmedova, founder

With this understanding, the group labored and plodded for months, diving deep into their cultural roots and personal experiences so that they could arrive at common cultural points shared across Central Asia that they could build the magazine around. It was important to create a magazine that “gives us an opportunity to connect” with history, culture and one another, Assanova said.

In the heart of Bishkek, in front of the Kyrgyz National University, stands a statue of Jusup Hass Hajib, the university’s namesake and author of Kutadgu Bilig, the 11th-century composition from which Edgu Bilig’s name is taken.

After deciding on their name, the five combed through and wrestled with dozens of Turkic and Persian terms found in literary works from the eighth century on. After months of back and forth, they finally settled on a phrase that captured the essence of what they felt symbolized the region and its peoples: edgu bilig, a phrase from the 11th-century mirror-for-princes composition Kutadgu Bilig, by Jusup Hass Hajib, who was born in the abandoned Karakhanid city of Balasagun, just outside of the Kyrgyz capital, Bishkek. According to Tynchtyk Chorotegin, a historian and founder of Muras Foundation, in Bishkek, from the name the group selected, “Edgu means nice, good, sincere, etc. Edgu bilig [therefore] means a very insightful/sacred knowledge,” akin to Kutadgu Bilig.

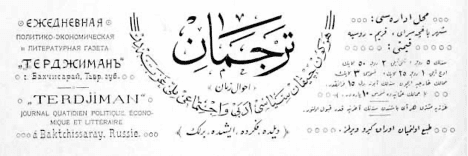

Once the name was agreed upon, Assanova, Akhmedova and the others then set out to piece together their vision for the magazine. They needed something that spoke of unity, a quest for improved understanding and enlightenment. So, the group rummaged through historic newspapers and magazines from Central Asia and sifted through publications in the West like The New Yorker and Harper’s Magazine, among others. But what they were seeking proved elusive. That is until something clicked within the group. To make the magazine into one they envisioned, the group would have to turn toward one of the most-impactful, historic publications from the region—Terjiman, the first Crimean Tatar newspaper, established by Tatar scholar Gaspar Ali in 1883.

In 1883, Tatar scholar Gaspar Ali established the first Crimean Tatar newspaper, Terjiman, shown in the image above of a header of one of its 1915 editions. Although the newspaper closed a few years later, it has continued to influence generations of Central Asians, including Edgu Bilig, which took inspiration from the newspaper’s mission statement. Photo Credit: Tarihresmi.blogspot.com

The group homed in on Terjiman’s mission statement, namely focusing on its expressed aim to write “about the life, lifestyle and needs of” its pages’ subjects: “Turks, Tatars, Azerbaijanis, Kumyks, Nugais, Bashkors, Uzbeks, Kashgars, Sarts, Turkmens, etc.” This much became obvious to the group: Edgu Bilig’s own value rested on them being able to deliver the humanity of the everyday person in Central Asia to readers worldwide. Edgu Bilig had found its voice, as the group resolved themselves to create a platform of “deeper understanding for the peoples of Central and Inner Asia,” according to their vision statement, “while inspiring everyone toward a more transformative, impacting future.”

But manifesting the meaning of Edgu Bilig has not come easy. It has taken more than a year to achieve. And in that time, Edgu Bilig has registered as a nonprofit organization, and experienced structural changes. Some of the original founders have since dropped off, but others have joined, expanding the group from five members to eight. Each new addition understood the potential behind Edgu Bilig, especially within a historical context.

Within early-20th-century Central Asia, newspapers were the only means of reaching larger populations over wider areas. It helped speed up the process of national identity and the need for cultural preservation. “Mass media was the only way to succeed, learn and, sometimes, was the only available source in regard to education,” said Assanova, stressing, “These [historic] newspapers [from the past] helped, educated, guided and united. I am sure without these newspapers we would never be able to save our identity, togetherness and save our memories.”

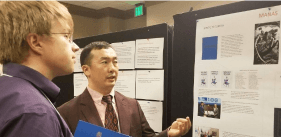

Mirlanbek Nurmatov, right, a Turkologist and business entrepreneur based in Chicago, presents glimpses of Kyrgyz history in the United States. Nurmatov joined Edgu Bilig in summer of 2022 as a partner. Photo Credit: Mirlanbek Nurmatov

Mirlanbek Nurmatov, joined Edgu Bilig in June of 2022. He sees the magazine’s potential in helping perform that identity Assanova pointed to newspapers saving. After earning his Ph.D. from the field of Turkology from Gazi University, Turkey, in 2016, Nurmatov found himself moving the same year to the United States with his wife and five children. Now residing in Chicago, he is busy preparing for the grand opening of his Harvest International Market, the first Central Asian grocery store in Chicago. As part of a growing diaspora of Central Asians within a society far different than his own, he points to the importance of preserving one’s cultural identity. And Edgu Bilig, he said, will allow that. For posterity, “we must allow our intelligentsia to grow,” he said, “We must protect our identity.”

Cultural identity, as the group views it, merges the living with the past. It is this understanding that fuels the group’s enthusiasm to tell their peoples’ histories and cultures through the stories of the living. And that remains part of the mission of Edgu Bilig: to share “vivid, inspirational storytelling centered on the peoples of the regions and their cultures.”

Abdrasul Isakov, a historian from Kyrgyzstan based in Ankara joined Edgu Bilig as a partner and oversees its community outreach initiatives. Photo Credit: Abdrasul Isakov

Abdrasul Isakov, a historian from Kyrgyzstan based in Ankara, and the magazine’s new director of community outreach, agrees. “Edgu Bilig,” he said, “undertook the mission of introducing the national consciousness, identity and worldview of the Central Asian countries to an English-speaking” audience, and this resonates with all the peoples from Central Asia.

Edgu Bilig is about good wisdom, knowledge, about our ancestors, about our history, all about us.Abdumalik Ganijonov, graphics design director

Abdumalik Ganijonov, a graphics and motions designer from Andijan, Uzbekistan, shown in this recent photo working content planning for clients, joined Edgu Bilig this past September. He brings with him experience in programming, photoshop, photography, filmmaking and graphics design. Photo Credit: Abdumalik Ganijonov

That type of personal worldview has motivated Abdumalik Ganijonov to join Edgu Bilig as a partner overseeing the magazine’s graphics team. A native of Andijan, near Uzbekistan’s southeastern border with Kyrgyzstan, the 21-year-old is busy at home working late into the night on the magazine’s new logo design. As a child, his father had taught him how to use a computer. For the past five years, he has combined that knowledge with his passion for fantastical movies, studying every scene with careful attention to recreate them. His interests have led him along a path connecting programming, photoshop, photography and filmmaking. And its’ only the beginning for Ganijonov. “I am not going to stop learning new things. I won’t InshAllah. There are still too many things to learn.”

And its with this quest for learning that Ganijonov aims to push forward Edgu Bilig. He dreams of helping it become one of the most successful online magazines in the world, not because of its graphics and photos alone. His hopes are rooted in a deeper understanding of culture behind the magazine’s name. “Edgu Bilig is about good wisdom, knowledge, about our ancestors, about our history, all about us,” he says, predicting “it will play a significant role in Central Asia.”

Nurtas Sissekenov, who, from Kazakhstan, joined Edgu Bilig as its creative director, agrees. He also believes Edgu Bilig has a much larger part to play at a global level. And its with that, he feels a sense of responsibility to see the magazine “become a platform that not only tells stories about Central Asia but creates an international community that … embraces ‘radical tenderness’ through collaboration, education … compassion.”

Zhapar Manas Uulu poses in Time Square, New York, in August 2021. After joining Edgu Bilig as a frontend developer in March 2022, Manas Uulu remarked that with Edgu Bilig’s digital experience, “there is no limit,” a mission he is committed to realizing. Photo Credit: Zhapar Manas Uulu

How Edgu Bilig goes about this depends largely on how it grows out its different platforms through social media and a dedicated website, as well as within workshops and community events. Overseeing the magazine’s frontend development is Zhapar Manas Uulu. At only 19 years old, Manas Uulu, is precocious and forward-looking. He sees the website’s growth as an opportunity to introduce the voices of Central Asia to an ever-expanding readership. “The digital experience helps people read stories any time, in any location, with any device that has internet,” he said. “There is no limit.”

Igor Shevtsov grew up in Kyrgyzstan, which informed his love for the great outdoors—as shown in this 2021 photo of him camping near Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. Shevtsov joined Edgu Bilig in 2022 determined to “make unique content digitally accessible” for millions. Photo Credit: Igor Shevtsov

Igor Shevtsov, who grew up in Kyrgyzstan and now lives in Chicago, agrees. With its priorities online, said Shevtsov, who became director of technology development, the magazine will thrive because it has set out to “make unique content digitally accessible,” for millions of people around the world.

But their quest to share quality human-interest feature stories depends on the availability of skilled writers from the region. The issue they confront is that Central Asian journalists are largely unfamiliar with feature writing. To tackle this, Edgu Bilig started providing workshops four times a year to train early-career journalists. Aidana of Kazakhstan is an undergraduate student specializing in digital history at the Kazakh National Pedagogical University named after Abai, in Almaty. She attended the magazine’s very first workshop, led by Alva Robinson, a Turkologist and assistant editor for AramcoWorld, this past April and feels she is ready to tell her people’s stories. “Now,” she said, “I know [as a journalist] that you need to look at the world through the eyes of the subject and to dig deeper.”

And that has been exactly what Akhmedova has imagined for Edgu Bilig since its inception. “It’s an entrance into a beautiful yurt and sitting down for a cup of tea with hosts on felted rugs and listening to their stories with an English interpreter,” she said.

Back at home in Almaty, Assanova shared the same sentiment. “It’s a kind of a very long way back in the search for roots,” she said, “but it works.”